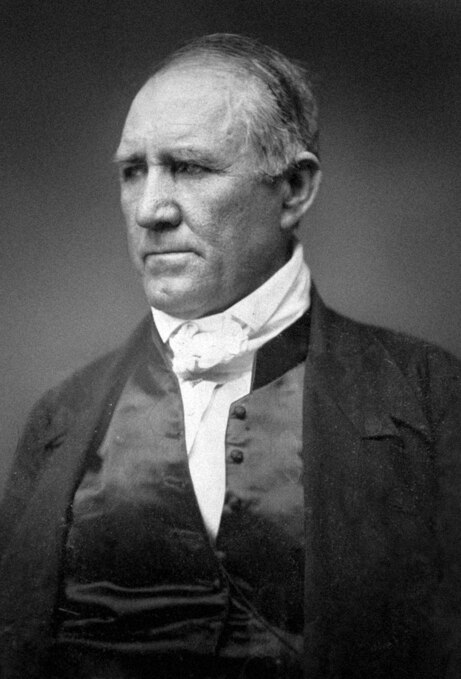

I enjoyed Tom Brokaw's book, The Greatest Generation, about my parents' generation. Those who lived through the Depression and then fought in World War II were special, but after learning about the people of the early 19th century, I think a better name for Brokaw's book would be "The Greatest Recent Generation." The people of the early 19th century were also a cut above those who followed them. Their courage and self confidence created the world we live in, and in that time of strong men and strong personalities, Sam Houston stands out as one of the strongest.

Sam Houston was born in Kentucky in 1793. His father died when he was 14, and his mother took him and her 8 other children to a homestead in Tennessee, where she managed a farm and a store. Sam didn't like farm work so he was put to work in the store. Soon tiring of that, he ran away and joined a band of Cherokee Indians, like my great great grandfather Smith Paul. Houston later commented that he preferred the freedom of the Indians to the tyranny of his brothers.

In his autobiography, Sam Houston describes with great respect the simplicity and virtue of the Cherokee. He learned the Cherokee language and was adopted by their chief, Oo-loo-te-ka, who gave Sam the name Co-lon-neh, the Raven. After three years with the Cherokee Sam returned to his home, and for a while worked as a teacher.

Houston tried for a while to further his education, but failing geometry he joined the Tennessee militia under Andrew Jackson. He joined just in time to take part in Jackson's massacre of the Creek Red Sticks at Horseshoe Bend in 1814 (see post of October 26, 2010). Unlike David Crockett, who was disgusted by the senseless slaughter, Houston was caught up in the excitement. When the first man over the breast works was shot in the head, Houston followed him and was shot with an arrow in the leg. When the arrow was removed Houston said he was ready to return to the battle. Andrew Jackson himself ordered him to remain in the rear, but Houston not only disobeyed Jackson's order, he volunteered to lead the charge against the Creeks' last bastion. He was shot twice in the shoulder, and then led the charge again. Houston survived in spite of his serious wounds, and his reckless heroism earned Jackson's respect.

Sam Houston returned home after the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, where he was nursed back to health by his mother. As soon as he was strong enough to ride a horse he went to Washington, DC, and asked to be commissioned into the army. Before he left Tennessee, his mother gave him a ring on which was engraved the word "honor." He wore the ring until his death. After a brief service in New Orleans at the end of the War of 1812 Houston was appointed Cherokee agent. He was able to convince his Cherokee "father," Oo-loo-te-ka or John Jolly, as he was known to white men, to move west to the Indian Territory with his followers. When the guns and blankets that were promised to the Indians weren't delivered, Houston led a group of Cherokees to Washington to complain. When he confronted John Calhoun, the secretary of War, Houston dressed as an Indian, in a blanket and a breechclout. Calhoun reprimanded him for not wearing his military uniform, and accused him of slave trading. Houston resigned his commission.

Now unemployed, Houston decided to return to Tennessee and to become a lawyer. He may have failed at geometry, but he had always been an avid reader. Houston began to "read" the law in the office of James Trimble in Nashville, Tennessee, and after six months he passed the bar and set up his own law office in Lebanon, Tennessee. There he became a regular visitor of Andrew Jackson who was at home recovering from his own wounds. In Lebanon, Houston ran for the office of prosecuting attorney and won.

Houston rose quickly in politics. He was elected Major General of the Tennessee militia and then senator. During his term in Congress he was involved in several conflicts including a duel. To remind John Calhoun, still secretary of War, of his previous insult, Houston presented him with a bill for $36 for his expenses as Cherokee agent. After his term in the Senate Houston returned to Tennessee, ran for governor, and won.

Then something happened for which there has never been a satisfactory explanation. Near the end of his term as governor, Houston married a young woman named Eliza Allen. Three months later he resigned as governor and boarded a steamship for Indian Territory with no other explanation than Eliza had been cold to him.

Once in Indian Territory, Houston rejoined his Cherokee father John Jolly, and began to drink heavily. Houston's friend Andrew Jackson was now president and Houston began writing letters to him complaining that the Indian agents were cheating the Cherokee out of their annuities, and white settlers were cheating them out of their land. He also was heard to boast that within two years he would conquer Mexico and become emperor of Texas. This sounds a little crazy, even for Sam Houston, but apparently Jackson took him seriously because he shot back a letter asking him not to go ahead with his plan.

In Indian Territory Houston built a home he called his "wigwam;" he opened a trading post and married a Cherokee woman. In 1829 he became a member of the Cherokee tribe and made a trip to Washington as part of a Cherokee delegation. While he was there he was invited to the White House to visit Andrew Jackson. After recommending to Jackson's Secretary of War, John Eaton, that he fire several Indian agents, he submitted a contract to provide rations for the Removal of the Five Civilized Tribes to Indian Territory. Houston was not awarded the contract, and he returned to his home among the Cherokees.

While operating his trading post, Houston was investigated by the commanding officer at Fort Gibson, Colonel Matthew Arbuckle, for selling liquor to the Indians, which was illegal. Houston himself had protested to Washington about the illegal liquor traffic to Indian Territory and its damaging effects among the Indians. When confronted with the enormous amount of liquor that he had purchased, Houston swore that all of it was for his personal use. Perhaps he was telling the truth. The Indians had given him a new name, it meant "big drunk" in Cherokee.

Houston led another Cherokee delegation to Washington in 1831. While he was there William Stanberry of Ohio accused John Eaton of conspiring to give Houston the contract to provide rations for the Removal. Houston challenged Stanberry to a duel, and when Stanberry didn't reply, Houston caught him on the street and beat him with his cane. Houston was six feet six and still a formidable man, in spite of his war injuries. Houston was put on trial by Congress for his attack. The trial lasted for a month and Houston was defended by Francis Scott Key. On the night before the trial's conclusion Houston went out and got drunk, then went to Congress the next morning and in spite of his hangover gave an eloquent speech in his own defense. Congress let Houston off with a $500 fine.

In 1831, one of the issues which attracted attention in the United States was Texas. After Mexico had won their independence from Spain they had been inviting Americans to come to Texas to settle. The number of settlers had grown to 20,000. The Texans were more loyal to the United States than they were to Mexico and there was much sentiment there for independence. Jackson had made some diplomatic efforts to buy Texas from Mexico but had been rebuffed. While Sam Houston was in Washington going through his spectacular trial, he had also been visiting the President, and they had talked about Texas. There's no record of whether they discussed Houston going to Texas, but this time when Sam Houston left Washington, he didn't return to Indian Territory. He went to Texas and joined a settlement headed by Steven F Austin, apparently deserting his Cherokee wife.

I think I'll skim over the details of Sam Houston's adventures in Texas. That part of his story is Texas history. He helped inspire Texas' fight for independence; he proved to be a shrewd general in his defeat of Santa Anna at San Jacinto, and when Texas became a republic in 1836, he was elected president. When Texas became a state of the Union, Houston served as a senator and also as governor. When Texas voted to join the confederacy, Houston resigned his position as governor and retired to private life, refusing to fight against the Union. Sam Houston continued to be a colorful character. He never gave up his independent spirit and he was always a friend of the Cherokees.

Sam Houston made his home in Natchidoches, Texas, close to a peaceful settlement of his old friends, the Cherokees. There was a terrible prejudice among the Texans against Indians, because of the depredations made against them by the plains tribes. It didn't matter to them whether or not the Indians had taken up civilized ways; it didn't matter to them whether or not they were living peacefully with their neighbors. In 1836, Sam Houston went out to Bowles Village, named after the Cherokee leader who had sought safety for his people in Texas twenty years before, and he made a treaty guaranteeing the Cherokees safety on the land that they occupied. In 1837 the Texas legislature refused to ratify the treaty, and in 1839 after Sam Houston had been replaced as President by Mirabeau Lamar, several regiments of Texas militia fell on the 1500 peaceful Cherokees and drove them out of Texas. After all his many accomplishments Houston couldn't protect his lifelong friends, the Cherokees.

Advancing the Frontier, Forman, P 165.

After I wrote the above summary of Sam Houston's escapades I began to doubt whether it belongs with a group of stories which try to look at history from the Native American point of view. I had first thought of putting it in because Houston's story has always been entertaining to me. He went recklessly from one adventure to another during his life, and he had the strength, the raw courage, and the intelligence to survive, even to succeed.

But something about the story of Sam Houston bothers me, and maybe it's because his personality highlights the attitudes of the white America of his day. On the one hand he appreciated the Indians' "simplicity." That was the same kind of grudging admiration that was given to blacks at the time. Houston was taken in and protected by the Cherokees as a rebellious teenager, and then proudly took part in the greatest slaughter of Indians in the history of this country. Later when Houston was having marital problems he turned to the Cherokees again, and to alcohol. As the "big drunk" he showed off his celebrity by taking them to Washington, where he tried to take advantage of their misfortune by applying for a contract to provide rations for the Removal, which was second only to the slavery system as the greatest travesty of human rights in our country's history. Then as soon as he got an opportunity for glory in Texas, he abandoned his Indian wife without a second thought.

I'm not saying that Sam Houston wasn't sincere in his gratitude and admiration for the Cherokee, and I am still entertained by his story, but perhaps the appeal of Sam Houston can give us a little insight into how such men could become heroes in their time, and how such attitudes could be rationalized.

No comments:

Post a Comment