|

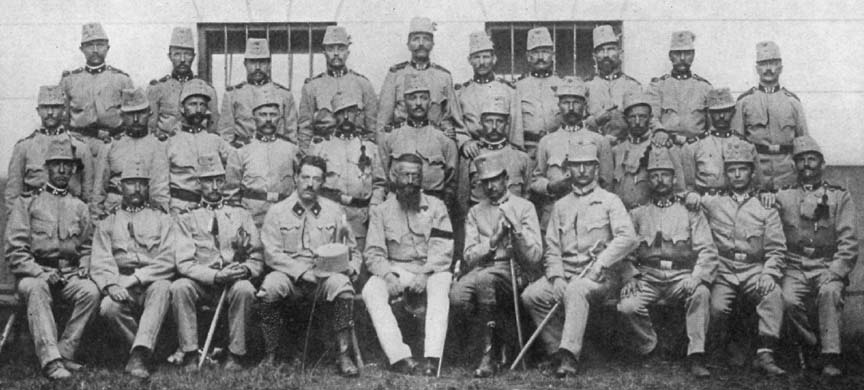

| Fritz Kreisler, WWI, Austrian Army, 1915, front row, to left of man with beard |

I don’t know why

exactly, but the last two books I’ve read have been about soldiers on the front lines. I guess it makes sense in a way because 2020 marks the 75th anniversary of the end

of WWII. There was an article in National Geographic commemorating WWII.

The books I read

didn’t have anything to do with WWII though. One was a memoir by George Orwell

who volunteered and fought in the Spanish revolution. With the modern rise of

nationalism, I thought the book might give me some insight into the dangers of

nationalism progressing to fascism. Actually Orwell’s memoir was more about

poverty and suffering, and the complicated politics in Spain during the 1930’s.

The other book I

read was by Fritz Kreisler, the famous violinist. Getting ready to play one of

his compositions, “Liebesleid,” I read that he had fought in WWI in the

Austrian Army, and that he had also written a memoir about his experiences,

“Four Weeks on the Front Lines,” so I ordered the book and read it on my Kindle

while waiting for my car to be serviced this morning. It’s a nice little book,

and quite an accomplishment. He apparently wrote it between concerts.

Anyway, one of the

stories he told was about interacting with the Russian troops while both sides were dug in about 200

meters away from each other. He said that with binoculars they could see the Russians so well that after a couple of weeks, they felt like they knew each other. One day one of the Russians, a big burly fellow, began to wave his arms and shout. Then, after a while, he stood up, in plain view, and when no one shot at him, he stepped out of his trench. Then one of the Austrian troops from Kreisler's side of the line stepped out in the open. No one shot at him either. Slowly, the two men walked toward each other until, finally, they were face to face. Neither was armed. Kreisler said he was thinking, "what are they going to do, have a fist fight?" Then the Russian reached into his pocket, pulled out a pouch of tobacco and handed it to the Austrian, who gave him a cigar in return. After exchanging gifts, the two men turned around and returned to their positions.

And this wasn't the only remarkable incident. About a week later, a Russian colonel stepped out from behind the trench line waving a white flag. The Austrians let him approach and then blindfolded him to take back to the Austrian commander. Kreisler was called back to interpret because he spoke French and the Russian could speak a little French. Anyway, the colonel had come to ask for food. He said that his men had had no food for weeks and were dying of hunger. So the Austrians, who hadn't much food either, passed around a big sack, each man putting in what he could, out of compassion for the Russians, who they realized, were in almost the same situation as they were.

Actually, Orwell expressed a similar sentiment. He said that after talking with prisoners fighting for the fascists, he realized that they were just poor peasants like those fighting for the revolution.

These stories took me back to Vietnam, where I spent a year of my life. I was stationed in the rear, so I can't relate to foxholes, gunfire and explosions, but I was acutely aware of the fighting going on. What struck me about the attitude those where I was, mainly officers,

was their casual attitude. It was one of my jobs to attend the general's weekly briefing where I reported the cases of malaria, plague, hepatitis, food poisoning, and what we were doing about it, and so I also heard the reports about how the war was going, how many casualties there were on our side and how many on theirs. The atmosphere seemed to me like that of fans at a football game. They were keeping score! Not only that, there was an attitude of contempt for the Vietnamese. The North Vietnamese were like animals, with no concern for human life, and the South Vietnamese were cowards, with no loyalty to their government.

At the same time, back at my office, one of my jobs was to interview the guys being sent home for some reason, a serious illness, or a family crisis. It had to be bad. The army was pretty strict about who they took in, but once you were there, it was really hard to get out. I had a young man with leukemia that I thought I'd never get home. Anyway, as I talked with the guys "on the line," so to speak, they showed a lot more respect for the Vietnamese than those in the rear. They realized that the Vietnamese were fighting with meager supplies, living in primitive conditions, and unlike our men, who could go home after a year's service, they couldn't go home unless they were badly injured or killed.

So, like the soldiers Orwell and Kreisler wrote about, those actually doing the fighting respected and sympathized with their enemies, while the politicians, and to some extent, the officers in the rear, dehumanized the enemy and trivialized the suffering and death that was happening to both sides.

No comments:

Post a Comment